Less than four days prior to trial we settled this medical negligence case against a hospital . This ended a fight for justice and fairness for our client and her husband which lasted over four years and culminated in a settlement that will pay out close to $6,000,000.00 in present and structured benefits.

The patient was then a 50 year old lady who had a complicated roux-en-Y procedure in that there was a complete blockage preventing the passage of anything from her mouth to her intestines. She was transferred to the larger more specialized hospital for treatment. A stent was placed to allow passage of food but the degree and extent of passage was never measured. The patient had multiple complaints of nausea and some vomiting over the next month or so.

The patient was then a 50 year old lady who had a complicated roux-en-Y procedure in that there was a complete blockage preventing the passage of anything from her mouth to her intestines. She was transferred to the larger more specialized hospital for treatment. A stent was placed to allow passage of food but the degree and extent of passage was never measured. The patient had multiple complaints of nausea and some vomiting over the next month or so.

She developed peripheral neuropathy, weakness and pain which started in her distal lower extremities and moved more proximal and started in her upper extremities. She developed ataxia and she fell due to her imbalance. She was admitted to a local small town hospital where many labs were obtained and a spinal tap was found to reveal normal spinal fluids. She was then transferred to the same large hospital for a work up of her symptoms. In the larger hospital it was noted that she had mental status changes and even had difficulty providing a consistent history and following two and three step instructions.

The Science of the Medicine

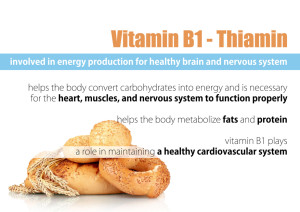

This patient had certain conditions and comorbidities, which created a known heightened level of risk for nutritional/vitamin deficits. Therefore it was paramount that the physicians maintain a heightened level of vigilance for vitamin/nutritional deficits and including laboratory surveillance of vitamin/nutritional status. It is well known in medicine that: gastric bypass patients have a heightened level of nutritional and vitamin deficiencies; that complications which affect nutritional intake heightens the risk of such deficiencies; that nausea and vomiting affects the amount of intake a patient has after gastric bypass surgery; and that peripheral symptoms that she had can be caused by nutrient/vitamin deficiencies, especially B12, B1, folate, zinc and copper. Here a low B1 lab result was obtained within days prior to her admission to the large hospital while the B12, folate, zinc and copper labs were normal. The patient’s low B1 lab result was transferred from the small hospital to the same large hospital which admitted the patient.

It is well known throughout all disciplines of medicine that a B1 deficiency is a significant medical emergency which will lead to permanent mental, cognitive and physical deficits and even death if untreated.

The Standards of Care applicable to this case:

1. When a post gastric bypass patient presents with peripheral symptoms the standard of care is to immediately administer B1 thiamine per a specific protocol. This standard is without regard to any B1 lab result as the results usually cannot be obtained in the necessary time frame to treat the condition emergently. You can test for B1, but start treating B1 immediately.

2. If you think the patient may have a B1 deficiency you treat with B1 thiamine as there is no downside to treatment and the damage from failing to treat such a deficit is devastating. So if you think of B1 you treat it.

3. If you have a low B1 lab result and the patient is having symptoms consistent with low B1 (even if the symptoms are consistent with other conditions), you treat with B1 emergently as the failure to treat can cause devastating injury and death. The condition is called dry beriberi and Wernicke Encephalopathy/ Wernicke Korsakoff Syndrome/ Korsakoff Psychosis.

Failure to Treat

In this case the physicians failed to treat low B1 or consider the patient as being B1 deficient. There was testimony that the B1 lab was not exceedingly low so the thought was that it was not low enough to cause her severe symptoms. B1 labs are notoriously inaccurate especially if the blood is not taken while the patient is fasting. Here the patient had eaten breakfast and lunch as an inpatient. No physician even considered a second test or treating the low B1 empirically. It is believed that the fact that most B1 deficient patients seen in the United States and other developed countries are chronic alcoholics. This may contributed to the failure of these physicians to recognize the thiamine deficiency in a non-alcoholic patient. This excuse or basis for the failure to diagnosis is not acceptable for many reasons. The service who treated the patient during the admission for the peripheral symptoms was neurology which is a very appropriate speciality to treat and diagnose the condition she developed from the B1 deficiency. When neurology could not identify a cause, even after a multi-million dollar workup (their words not ours) they failed to consult with the bariatric surgeon who previously treated the patient for the surgical complication.

While she was still undiagnosed, the patient was transferred to facilities with a lower levels of care.

The patient was transferred to a facility on the level of a rehab care facility. The patient’s cognitive/mental condition worsened as her nutritional intake worsened to the point that she was less oriented, in more pain and was more confused. She was deemed to be not a candidate for rehab and was sent to a lower level of care at a skilled nursing facility. There, the patient became worse to the point that her pupils became fixed and dilated. Her food intake was less and less. She began to hallucinate. She was eventually diagnosed with Wernicke’s Encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s psychosis. The original large hospital never called the patient for the follow up visit that was promised to occur after her nerve biopsies were completed. This visit fell thought the cracks.

Leave a Reply